News Story:

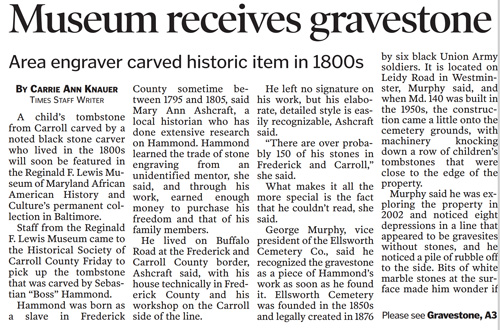

A child’s tombstone from Carroll carved by a noted black stone carver who lived in the 1800s will soon be featured in the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture’s permanent collection in Baltimore.

Staff from the Reginald F. Lewis Museum came to the Historical Society of Carroll County Friday to pick up the tombstone that was carved by Sebastian “Boss” Hammond.

Hammond was born as a slave in Frederick County sometime between 1795 and 1805, said Mary Ann Ashcraft, a local historian who has done extensive research on Hammond. Hammond learned the trade of stone engraving an unidentified mentor, she said, earned enough to money to purchase his freedom and that of his family members.

He lived on Buffalo Road at the Frederick and Carroll County border, Ashcraft said, with his house technically in Frederick County and his workshop on the Carroll side of the line.

He left no signature on his work, but his elaborate detailed style is easily recognizable, Ashcraft said.

“There are over probably 150 of his stones in Frederick and Carroll,” she said.

What makes it all the more special is the fact that he couldn’t read, she said.

George Murphy, vice president of the Ellsworth Cemetery Co., said he recognized the gravestone as a piece of Hammond’s work as soon as he found it. Ellsworth Cemetery was founded in the 1850s and legally created in 1876 by six black Union Army soldiers. It is located on Leidy Road in Westminster, Murphy said, and when Md. 140 was build in the 1950s, the construction came a little onto the cemetery grounds, with machinery knocking down a row of children’s tombstones that were close to the edge of the property.

Murphy said he was exploring the property in 2002 and notices eight depressions in a line that appeared to be gravesites without stones, and he noticed a pile of rubble off to the side. Bits of white marble stones at the surface made him wonder if any gravestones might be buried within the rubble, so he started to dig.

Less than a foot under the pile, he found the Hammond-carved gravestone, he said, about two feet long and a foot wide and just as easy to read as the day it was carved.

Hamond generally used stone harvested from Sam’s Creek in the New Windsor area, said Timmi Pierce, executive director of the Historical Society of Carroll County.

“He could carve stones like nobody else,” Pierce said of Hammond. “And those stones seem to maintain quality better than anything I’ve ever seen.”

The Ellsworth Cemetery Co. kept the Hammond stone on site until last year, when they decided to work with the Historical Society to find an organization they could donate it to where it would be on display for all of Maryland to appreciate.

Ashcraft said the Carrol and Frederick county historical societies each have an example of Hammond’s gravestones, as did the New Windsor Heritage Committee and the Maryland Historical Society. While the Reginal F. Lewis Museum had a shard of a Hammond gravestone – the decorative tip of a broken stone – the Historical Society and Ellsworth offered to give it this new piece.

The gravestone is in two pieces with a third piece still missing, but is has most of the writing on the stone visible, except for the year that the child died.

Murphy said there’s another significant factor that makes this gravestone special. Because the Ellsworth Cemetery was an all-black cemetery through the 1800s, and most of the 1900s, they know that the stone belonged to a black child – the only Hammond-carved gravestone that they know of that he created for a black person, besides the ones he carved for himself and his wife. Murphy said they believe it belonged to the child of one of Hammond’s friends.

Michelle Joan Wilkerson, director of Collections and Exhibitions at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum said the staff was happy to receive such an important piece of Maryland’s African American culture. She said the museum is looking forward to highlighting the example of Hammond’s work, as well as his story about how he used his trade to buy his freedom.

Alice Green, Union Memorial Baptist Church historian, said she was glad t see the gravestone go somewhere that it will be protected and appreciated.

“When you think of the desecration of a lot of cemeteries, it’s just sinful,” she said. “It’s wonderful [to protect this piece], I’m very excited.”